With the number of offshore wind farms in European waters, and elsewhere, set to rise dramatically in the coming years, it is critical that the implications for wildlife are fully considered. Birds, in particular, are at risk through collisions, barrier effects and habitat loss.

There is a growing political impetus to reduce anthropogenic carbon emissions. Wind power has emerged as a leading renewable technology and is currently the fastest growing source of energy in the world. By the end of 2008, wind turbines were satisfying more than 1.5 % of the world’s electricity demand, generating 260 TWh annually (WWEA 2009).

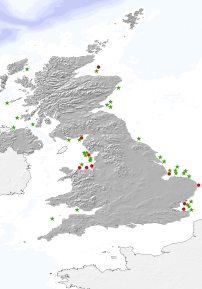

In Europe, there has been a rapid proliferation of wind farms in the marine environment, which may portend a global trend. Within European waters, there are currently some 160 offshore farms either in operation, under construction or being planned. At the forefront of this expanding industry is the United Kingdom with ten operational wind farms made up of 203 turbines, and plans for a further 7,000 turbines by 2020 (see figure). The United Kingdom, together with Germany, currently accounts for around 60 percent of the global offshore wind market (WAB 2009). Although more costly than their terrestrial counterparts, offshore wind farms have a number of advantages. Winds at sea tend to be stronger and more consistent, and weighty turbine components are more easily transported at sea permitting larger turbines to be constructed (European Commission 2008). In addition, offshore wind farms typically encounter less resistance from local communities (Dolman et al. 2003).

Also, during their seasonal migrations, huge numbers of passerines cross Europe’s seas mostly at night and at a low altitude. It is inevitable that birds will collide with turbines, particularly under adverse weather conditions with poor visibility (Hüppop et al. 2006). Thirdly, several studies have found that offshore wind farms act as barriers to travelling seabirds. Displacement from their favoured routes is likely to increase travel distances, causing greater energy expenditure and potentially impacting the survival of nestlings by lowering provisioning rates (Petersen et al. 2003, Fox et al. 2006). For example, at the Nysted offshore wind farm in Denmark, travelling birds (particularly seaduck) displayed profound avoidance behaviour, with the number of birds entering the area declining dramatically following the construction of the wind farm (Desholm and Kahlert 2005). (Editor’s Note: the article initially implies that wind turbines create meaningful electricity. They do not. Net zero world wide. That is a fact)