ENDANGERED SPECIES CONSERVATION

North Atlantic Right Whale Calving Season 2023

All the more reason to STOP any development of wind turbines offshore. STOP. Does endangered still mean “endangered”? OUR NOTE

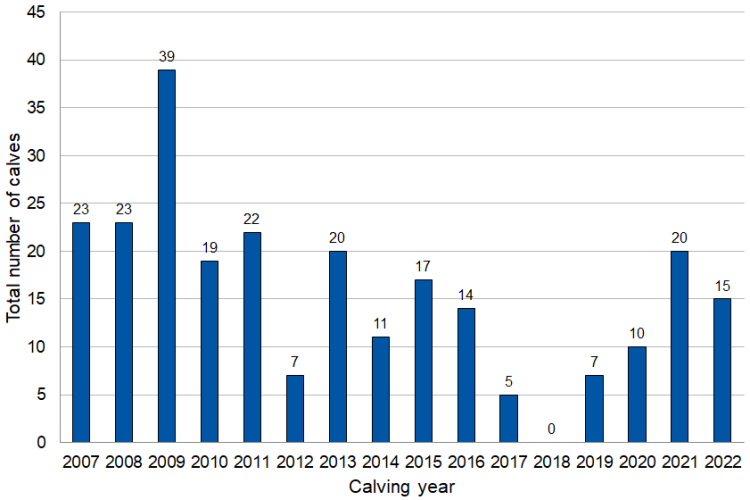

We estimate there are fewer than 350 North Atlantic right whales remaining. With so few of these whales left, researchers closely monitor the southeastern United States for new offspring during the annual right whale calving season.

Every single female North Atlantic right whale and calf are vital to this species’ recovery. So far, researchers have identified 11 live calves this calving season. Check back here or follow NOAA Fisheries on Twitter for updates.

North Atlantic right whales are dying faster than they can reproduce, largely due to human causes. Since 2017, the whales have been experiencing an Unusual Mortality Event, which has resulted in more than 20 percent of the population being sick, injured, or killed. The primary causes of the Unusual Mortality Event are entanglements in fishing gear and collisions with boats and ships. Researchers estimate there are fewer than 70 reproductively active females remaining. The remaining females are producing fewer calves each year, which impacts the ability of the species to recover.

Meet the Mothers and Calves of the 2023 Season

Every identified North Atlantic right whale has an assigned four-digit number in the Right Whale Catalog. Researchers assign names to whales that have a unique physical feature or a strong story in connection to a community or habitat where they were seen.

North Atlantic right whales are dying faster than they can reproduce. That’s why every whale counts. With the current number of females and the necessary resting time between births, 20 newborns in a calving season would be considered a relatively productive year. However, given the estimated rate of human-caused mortality and serious injury, we need approximately 50 or more calves per year for many years to stop the decline and allow for recovery. The only solution is to significantly reduce human-caused mortality and injuries, as well as stressors on reproduction.

Spindle (#1204)

North Atlantic right whale #1204, also known as “Spindle,” and her calf were sighted on January 7, 2023 east of St. Catherines Island, Georgia. Spindle is at least 41 years old and this is her tenth documented calf. She has now had more documented calves than any other right whale! Despite being the most prolific right whale mom we know of, only two of her known calves are female, and she only has one known “grand calf.” Spindle was named for the callosity pattern on her head, which resembles a traditional baluster, or spindle, on a staircase.

Unfortunately, scientists sighted Spindle’s 2019 female calf (#4904) with a severe entanglement and in poor body condition on January 8, 2023. Visit our North Atlantic Right Whale Updates page to learn more.

Pilgrim (#4340)

Beachgoers spotted a right whale and her calf on December 30, 2022, just offshore Canaveral National Seashore in Florida. The beachgoers reported the sighting to the Marine Resources Council’s right whale volunteer sighting network hotline. The Marine Resources Council, a NOAA Fisheries partner, was able to identify the mother as right whale #4340, also known as “Pilgrim.” She is 10 years old and this is her first known calf.

After this mom-calf pair’s initial sighting, the two have continued to travel southward. On January 4, 2023 the pair was seen near St. Lucie Inlet, Florida, which is further south than right whales typically travel.

Pilgrim was named after her initial sighting location; she was first seen as a very young calf with her mother, “Wart,” in Cape Cod Bay, near Plymouth, Massachusetts. Researchers think she was born in the Northeast instead of the typical right whale calving grounds in the Southeast United States.

War (#1812)

North Atlantic right whale #1812, also known as “War,” and her calf were sighted on December 29, 2022, about 11 nautical miles off the St. Marys River bordering Georgia and Florida. This right whale mom is at least 35 years old and this is her seventh documented calf. One of her two known female calves is presumed to be dead. Researchers see three of her offspring regularly, including the other female, born in 2016, who survived a severe vessel strike when she was young. War was named after the War of 1812 and for the callosities on her head—knobby white patches of rough skin—that resemble cannons.

Viola (#2029)

A survey team from Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute spotted “Viola” and her newborn calf on December 29, 2022, approximately 9 nautical miles east of Amelia Island, Florida. Viola was named for the shape of the callosity on her head, which resembles the stringed instrument.

Viola is 33 years old and this is her fourth documented calf. Her last known calf was born in 2011. Three years is considered a normal or healthy interval between right whale births. But now, females are having calves every 7 to 10 years, on average. Biologists believe that the stress caused by entanglement in fishing gear and collisions with boats and ships is one of the reasons that females are calving less often or not at all.

When Viola was sighted entangled in fishing gear in 2007, trained responders were able to partially disentangle her, which allowed her to shed the remaining gear.

Aphrodite (#1701)

A survey team from Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute spotted “Aphrodite” and her calf east of Nassau Sound, Florida on December 29, 2022. She is named for the Greek goddess of love; she has a heart-shaped scar on her side. Aphrodite is 36 years old and this is her seventh documented calf. Two of these calves are female, and both have gone on to calve themselves—She has four known “grand calves.” .

Smoke (#2605)

A Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute survey team spotted “Smoke” and her calf about 15 nautical miles east of St. Catherines Island, Georgia on December 26, 2022. Smoke is 27 years old and this is her fourth known calf.

In November, an aerial survey team spotted Smoke with another reproductive age right whale female, “Caterpillar,” off the southern coast of Virginia. A HDR, Inc. research team supported by the U.S. Navy successfully attached a short-term suction cup tag to Smoke to collect detailed movement and dive data, audio recordings of the whales’ vocalizations, and high definition video. This tag was an important opportunity to learn more about the behavior of migrating right whales. The tag was programmed to release from the animal within 24 hours, at which point the researchers tracked it down.

Porcia (#3293)

A survey boat team from Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute spotted “Porcia” and her calf southeast of Ossabaw Island, Georgia on December 17, 2022. Porcia is at least 26 years old and this is her third known calf. Her first calf, right whale #3893, died in 2018 at the age of 10, when she was just entering the reproductive period, after being chronically entangled in fishing gear. Porcia’s second calf, #4193, was born in 2011. He was just two years old when he was found dead, entangled in fishing gear.

#1711

A survey team from Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute sighted right whale #1711 and her calf east of Cape May, Georgia on December 17, 2022. #1711 is 36 years old and this is her fourth documented calf. Her other known offspring, all male, are Bridle (#3311), Calanus (#3996), and Whirligig (#4711). #1711 was born during the 1987 calving season and was the first documented calf of #1710, who went on to have three more documented calves.

Archipelago (#3370)

A survey team from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission sighted right whale #3370 and her calf on December 8, 2022 off Little St. Simons Island, Georgia. Also known as “Archipelago,” this right whale mom is at least 20 years old, and this is her third known calf. She had her first known calf in 2009, and her second during the 2019 calving season. Her 2009 male calf was sighted fairly recently, in 2021.

Medusa (#1208)

A survey team from Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute sighted the first mother-calf pair of the right whale calving season on December 7, 2022 off St. Catherine’s Sound, Georgia. Medusa is at least 42 years old and this is her seventh documented calf. Her last known calf was born in 2012. The survey team was able to collect a biopsy sample that will be used to genetically determine the sex of this new calf.

Other Births

On January 3, 2023, a newborn male right whale calf was sighted near Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina. Despite an intensive search, researchers were not able to locate its mother. On January 7, 2023, the calf was found dead. Response teams recovered the carcass and conducted a necropsy, or animal autopsy. Visit our North Atlantic Right Whale Updates page to learn more.

Right Whale Reproduction

The right whale calving season begins in mid-November and runs through mid-April. Female right whales become sexually mature at about age 10. They give birth to a single calf after a year-long pregnancy. Three years is considered a normal or healthy interval between right whale births. But now, females are having calves every 7 to 10 years, on average. Biologists believe that the stress caused by entanglement in fishing gear and collisions with boats and ships is one of the reasons that females are calving less often or not at all.

Calving Area

Each fall, some right whales travel more than 1,000 miles from their feeding areas in the waters off New England and Canada to the shallow, coastal waters of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and northeastern Florida. The southeastern United States is the only known area where right whales regularly give birth and nurse their young.

NOAA Fisheries has designated two areas as critical habitat for North Atlantic right whales, including off the southeast U.S. coast from Cape Fear, North Carolina, to below Cape Canaveral, Florida—an important nursery and calving area.

Monitoring Right Whales with Aerial Surveys

A number of government agencies fund and conduct right whale aerial surveys between North Carolina and northeast Florida during the calving season. These agencies include the Army Corps of Engineers, Coast Guard, Navy, NOAA, and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. All of these aerial survey teams:

- Monitor the seasonal presence of right whales and their habitat use

- Alert mariners, boaters, and partners to the whales’ locations

- Monitor calf production

- Provide sighting support for biopsy efforts

- Detect and respond to reports of dead, injured, and entangled whales

Other key partners in monitoring the right whale calving area include Clearwater Marine Aquarium, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and the New England Aquarium.

Collecting Genetic Samples to Identify Right Whales

Boat-based teams from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission collect biopsy samples from right whale calves and other right whales that haven’t been previously sampled. You can think of these biopsies as similar to blood samples you provide to personal genetic DNA testing companies to learn about who you are and your family relationships. Identifying as many individual right whales each year as possible is crucial for monitoring the population; data on individual whales are used in models that estimate the total number of right whales.

How You Can Help: Go Slow and Stay Alert for Right Whales

Calving season is an especially vulnerable period for these whales. Despite their enormous size, North Atlantic right whales can be very difficult to spot from a boat due to their dark color and lack of a dorsal fin. This is especially true in poor weather and sea state or low light conditions. Mother-calf pairs are at heightened risk for vessel strikes because these individuals spend nearly all their time at or close to the water surface, but are difficult to see. Most boaters who reported striking a right whale didn’t see the whale prior to colliding with it.

Right whales have been injured or killed by all types and sizes of vessels—from recreational boats to large ocean-going ships. Additionally, disturbance from watercraft or aircraft could affect behaviors critical to the health and survival of the species. It is extremely important for all mariners and boaters to slow down, stay alert, and give these whales plenty of room.

Go Slow—Whales Below

Slower speeds are known to reduce the severity of impacts when collisions with whales occur and may provide boat and vessel operators an opportunity to avoid a collision. For most vessels 65 feet or longer, mandatory 10-knot seasonal management areas went into effect on November 1 between Rhode Island and Florida. Additional seasonal management areas off Massachusetts become active on January 1, 2023. NOAA Fisheries strongly urges mariners operating vessels 35-65 feet in length to transit at or under 10 knots within active seasonal management areas, in light of the danger posed to right whales by smaller vessels and NOAA Fisheries’ proposed changes to the vessel speed regulations.

In advance of your trip, check the NOAA Right Whale Sightings Advisory System or the Whale Alert app for active right whale safety zones, including seasonal and dynamic management areas, and right whale slow zones, and recent whale sightings near your location.

Learn more about U.S. vessel speed regulations and programs for right whales

All boaters from Maine to Virginia, or interested parties, can sign up for email or text notifications about the latest right whale slow zones.

Be On the Lookout

Post a lookout. Watch for black objects, white water, and splashes. Avoid boating in the dark or in rough seas, when visibility is poor.

Give Right Whales Space

Federal law requires vessels, paddle boarders, and aircraft (including drones) to stay at least 500 yards (five football fields) away from right whales. Any vessel within 500 yards of a right whale must depart immediately at a safe, slow speed. These restrictions are in place to prevent accidental collisions between right whales and boats as well as to protect the whales from disturbance.

The Right Stuff: Regulations for Right Whales

North Atlantic right whales are one of the world’s most endangered large whale species, with only about 450 remaining. NOAA has developed regulations for boaters and fishermen to help protect these whales from vessel collisions and entanglements.SharePlay Video

To report a right whale sighting from North Carolina to Florida, or a dead, injured, or entangled whale, contact NOAA Fisheries at (877) WHALE-HELP ((877) 942-5343) or the Coast Guard on marine VHF channel 16. Please report sightings from Virginia to Maine by calling (866) 755-6622. If safe, and from the legally required 500-yard distance, please take a photo and note the GPS coordinates to share with biologists.

More Information

- North Atlantic Right Whale Road to Recovery

- North Atlantic Right Whale Updates

- Right Whale Calving Season 2022

- Go Slow—Whales Below

- Podcast: Slowing Down to Save Right Whales

- Latest Right Whale Sightings

Last updated byOffice of Communicationson 01/12/2023

PLEASE ALSO SEE:

Plain Stupid: The Only Thing Dumber Than Wind Power Is Offshore Wind Power